obwohl ich sonic youth nicht leiden kann, mag ich mike kelley, der aus ihrem umfeld heraus durch kunst mit kuscheltieren populär wurde.

(als ich in den 90ern ein plakat sah, wo er auf einem schrubber lehnt, dachte ich: das ist einer von uns - und siehe einige jahre später, nach bekanntschaft mit seinem musikalischen frühwerk: spässe lügen nicht.)

ostrich,

Donnerstag, 1. April 2010, 16:25

To the Throne of Chaos Where The Thin Flutes Pipe Mindlessly

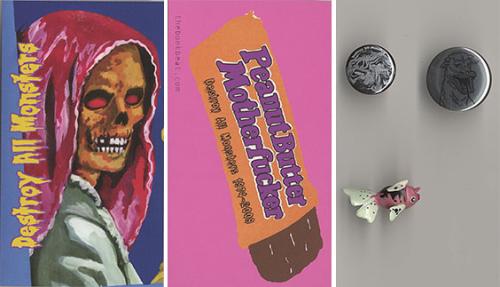

(Destroy All Monsters: 1974/77)

Some thoughts on the period of transition from progressive rock to punk rock, in the form of liner notes for a three CD box set.

PART 1

Music is eternal; it is ahistorical. So says the polliwog. Music in time is Muzak: floating strains, the meaningless pap that provides the background soundtrack for other peoples lives. It lies behind those that have history, who are old. Like embarrassing cartoon music, this mush shows its age and, in an amusing way, provokes disgusted looks on the enfeebled listeners who are familiar with it, who once thought that it was impervious to cooption. How pathetic . . . to hear these once "hot" sounds demoted to punctuation for children's entertainments, to be made present again . . . but only for the pre-adolescent. This is what happened to Raymond Scott's "Powerhouse" when applied to Bugs Bunny, when Cab Calloway crooned along with Betty Boop, and even now when Jimi Hendrix, in his death, supplies the soundtrack for today's "adult toy" car commercial. It is said that the old always return to their original childlike state, unless they are lucky enough to die first; they sink back to the square-one level of powerlessness. This deflation in caused by the realization that one is in time. Then the potent fuck beats of your prime become limply infantile. I am speaking now from the vantage- point of the old frog. And I tell you, once you have a music history these observations are painful and obvious facts. To the young soul these are incomprehensible notions. To these naives, music is of the moment. There is evolution, but in a constant present . . . always in a state of becoming. Changing reactions to music, and conscious improvements in taste, are not made in reference to a time before but are simply realizations that something could, not . . . be different, but better. New music is an outgrowth - a living thing emerging from a vibrant parent body and not a sickly response to that which has passed away. These sad observations are provided as an around-about way to introduce the genesis of a band, a band that never was - Destroy All Monsters, and to reveal some of the problematics of that attempt.

For me, these old recordings from 1974/76 are still very present. When I listen to them I am again back at their point of creation - because they never came to a conclusion. The "history" that they are part of is not yet written, at least not adequately. I am quite aware of the reasons for their production, and also the reasons why they are, perhaps, failed attempts. I also realize that the general listener will, more than likely, not understand them at all. This puts me in the position of having to construct a history for them, to set them up to age. And I sincerely hope they do become familiar enough to suffer the embarrassment of their position in time . . . to be used in cartoons and soft drink commercials. Why not? Everything else has. To set this process in motion means I must separate myself from my "pure" experience of this noise (which I hope still has the capacity to move other listeners in some approximately similar "pure" sense). I will now attempt to explain these recordings into historical importance, and through this explanation convince you that they are not mere kitsch, that they are still alien enough to be worth examining.

Destroy All Monsters is a band that never was, because it is a band that has become historicized (whatever minor history it does have) in an incorrect way. Destroy All Monsters is generally a footnote in the history of American Punk rock. It has been described in terms of, either, an American proto-Punk history (as an outgrowth of the Stooges because of the presence of ex-Stooges guitarist Ron Asheton in the line-up starting in the late 70s); or as a post-British Punk reaction . . . as one of the many bands to spring up in the States in response to the Sex Pistols. These pigeonholings are dependent on the point in time in which the chronicler became familiar with the band, and also their knowledge of American pre-Punk rock music. To many writers, Punk history is automatically a British history, and whatever manifestations of it that may have occurred in America are only twisted reflections of the real thing. In a sense I agree with this interpretation. The American bands that were influential in the development of British Punk: the Stooges, the New York Dolls and the Ramones, were indeed minor American bands in there own times, without any of the celebration and critical response that the Sex Pistols garnered. And second-string American Punk, especially California Hardcore, was obviously more of an outgrowth of the media-conscious and fashionable Sex Pistols than Midwestern and East Coast garage rock of the late 60s and early 70s. I know this for a fact since I was in L.A. in the late 70s. The scene was primarily Glam oriented when Punk hit, like a disease - a British germ that infected everyone overnight. One day there was no Punk, the next day the city was crawling with torn-clothed, safety-pinned spike heads. In any case, this discussion of Punk as the British Invasion of the late 70s has little to do with Destroy All Monsters, which was already in existence in 1974. We were completely ignorant of the British underground musical developments then in a protean neighborhood state of development . . . just like we were. Warning! To all Anglophiles, this is a history that predates the American popularization of punk. And this history only finds its flowering in a later, supposedly post-Punk development - namely, Industrial music. Warning! Also to Stoogeophiles. This is a history of Destroy All Monsters before the arrival of Ron Asheton. Stooges fan club members will not find any missing nuggets of wisdom here.

To understand Destroy All Monsters one must put themselves into an early 70s mindset. The first wave of alternative rock, and by this I mean the incredible outpouring of garage Psychedelia in the late 60s, was long dead by this time. Musically, this was the era of broken promises. The psychedelic avant-garde vision of a new Pop Music to mimic the new social experiment had proven a pipe dream. There was the sense of living in the decadent twilight occasioned by this fall. And in the mindless flight from this Altamontian negativity a wave of escapist feel-good pap became the dominant musical trend. The music scene was dominated by pseudo-back-to-folk-roots ballads of the James Taylor (or one of his innumerable siblings) variety. The thunderous counter-movement to this laid-back sound was prole-rock. Heavy Metal, despite its surface difference from Folk and Country rock, was similarly "roots rock", though admittedly a more high energy and body-conscious version of it. Yet, it was still a music that was meant to console "the people", not confront them.

In this cultural Suburban wasteland there was only isolation, and a sense of being betrayed. The strange brew of avant-garde experimentation and populism of late 60s acid rock had failed in its social promises. To someone of my age (too young to be a hippie, to old to be a punk) there was definitely a feeling of resentment at having missed the short hedonistic flowering of this dream. These fantasies were only then available on records stolen at K Mart or the mall along with other packaged fantasies: Conan the Barbarian novels and other adolescent juvenilia. And by the time you got these records, the "stars" who made them were already in decline: dead, drugged out, or producing corporate rock. Where was my utopia? Where was my free sex? Nowhere to be seen. It only existed in a corporate dream of packaged freedom, in the pathetic sense that thirteen-year-olds wish to be the eighteen-year-olds they see in movies - movies like "Pretty Poison," where hot teen-age girls snuff their parents and put the blame on a nerd. But, I was the nerd. Because of this overall mood of betrayal, rock music was something to be abandoned and left to the dolts: the new armies of ex-high school football players, now hipster longhairs, who filled stadiums to see "righteous" acts like Grand Funk. In revenge for this betrayal, in revenge for the popularization of rock music, for the rise of arena rock, for the rise of country rock, the most moronic musics of the progressive acid rock period of the late 60s all of a sudden seemed its most important products. The thuggish sounds of the Stooges, Blue Cheer and the insipid acid-whinings of the Seeds revealed the pomposity of the "grand experiment". Thirteen-year-old-music of the late 60s became more important than the technically superior and politically savvy music of the twenty-year olds. "Progressive" English and San Francisco rock was abandoned. Inspirational noise had to be found elsewhere. Even in high school, before any of the self-conscious "criticality" of college, I had these leanings. Even then, I found myself tiring of rock music and explored it in its furthest outposts, where the definition of "rock" was stretched beyond recognition. Noise fests like the weird "songs" by Silver Apples, the more annoying Pink Floyd tunes like "Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun", the MC5s "Starship", the Stooges "L.A. Blues", the Mothers of Invention' "Weasels Ripped my Flesh" the Velvet Underground's "Sister Ray" were my preferred listening. These oddities led to the realization that there was "another" history behind these records, a much more brutal, and anti-pop, history that deserved looking into. Brutality, cutting through the pop boundary line, seemed to be the order of the day. Thus I was led to Sun Ra, Morton Subotnik, Harry Partch, Lamont Young, John Cage, Stockhausen, Dadaist Bruitism, and the Futurist noise music theories of Luigi Russolo. Rock was a thing of the past. Disco music was already starting to eclipse it in popularity. I was convinced that what had been interesting in Rock all along was just the volume, your physical response to it. Everything else was just packaging - the marketing strategies necessary to sell pop product.

Georgio Morodor was God and Donna Summer his feminine voice, a voice that only feels the need to speak in orgasms. The first time I heard "I feel Love", it was a revelation. Here was a pure example of pop strategizing. All musicianship was removed; all pretenses to avant-garde theorizing as exemplified by rock acts like the Jimi Hendrix Experience which, to preach their message of freedom, had to make the listener un-free. By that I mean . . . Progressive Rock required a god-like technician, a skilled adept that, like the catholic priest, was a necessary intermediary between you and the "truth". This focus on technical expertise produced the "Rock God" - the guitar hero. Though, at this point, before the rise of codified Heavy Metal guitar worship, there was still a symbiotic relationship between musician and listener. In psychedelic music this relationship centered on feedback and random noise, which equalized musician and listener. Feedback was a sign that the musician was out of control, and the musician and listener shared equally in their experience of this out-of-control state. Feedback was the revolutionary component of acid rock, the anarchic sign of revolutionary freedom. It is the product of the electric instrument monitoring itself, and this self-examination leads to a breakdown of control that is evidenced in the mantra of the feedback loop - the technical equivalent of the acid trip. This was the same sound produced by the Free Jazz saxophone player. The instrument becomes the voice speaking in tongues; it is a pure extension of the voice. The wail of the saxophone is the voice and instrument mirroring each other, eyeing each other, feeling each other out until the one and the other are indistinguishable.

After the fall of the acid rock religion and the loss of faith in its revolutionary signifiers feedback, as a sign, became suspect. The voice no longer seemed an especially true voice. In Morodor's Techno Pop, feedback is synthesized, is domesticated, it becomes pseudo-feedback. What had been hot became cool. And with this change the various categories of rock music as they had existed no longer made sense. Progressive rock became "art" rock - that is, "fake" rock. The digital sequencer roar of Georgio Morodor is feedback harnessed, anarchy pantomimed a confusing contradiction of terms. It is push button rebellion. Yet, oddly, pseudo-feedback still has the same physical effect on the listener as the real thing. Now, the rock god became disposable and the religified communion produced by the relationship between musician and listener, the unequal relationship of devotee to idol, could be rejected. In progressive rock, the technical virtuoso allows you to commune with god only through them. They reveal their equality with you through the symbolic "failure" of feedback. Their "mistake" reveals them, like Jesus, to be also mere man. But with the mechanization of chaos there is no need of a technical virtuoso to symbolically fail. Everyone is equalized automatically because no technical skills are needed. And with this erasure of upper and lower, so also the mystical aspects of rock music are undone. Rock becomes materialistic; its effects have to be explained in somatic terms. If some rock was still "progressive" this term must now be expanded to accommodate market discourse. The question now is: what separates progressive materialist rock from corporate materialist rock?

With the demystification of rock music, its "artistry" shifts away from its truth-value to its codes of irony. The new cognoscenti are those who are steeped in the dictionary of the signs of rock's commodification. Rock stripped of its political trappings becomes, like early rock and roll of the Chuck Berry sort, linked with the purely hedonistic. Except that it is no longer associated with the lower classes, it becomes an intellectual property. This is implicit in the ironic Eurotrash posturings of Roxy Music. Rock now is simply a sign of the "trendy"; it is pure image. Rock becomes a word put to something to signify its acceptability. Avant-garde bands like Tangerine Dream and Kraftwerk all of a sudden were acceptable to large audiences of teens once they packaged themselves as a rock bands and separated themselves from the intellectual ghetto of electronic music. After "I Feel Love" it was apparent that all you needed to produce a pop hit was a machine rhythm and a sexualized image. Techo Pop (and Punk, Techno Pop's sloppy cousin) were born. Punk was born out of this same freedom from virtuosity. Punk shared Techno Pop's rejection of virtuosity, but also rejected the intellectual removal and irony of this gesture as seen in Art Rock bands such as Roxy Music, Kraftwerk and Devo. Anti-virtuosity was a democratic, populist gesture in favor of a decadent one. The pop hooks and guitar solos of prole rock might have been dismissed, but not the class affiliation, and the musical signifiers of that class: guitar, bass and drums.

The German bands were the most willing to play with and extend rock signifiers, perhaps because it was not a music born there and the class ties were not so strong. In the early 70s German trance bands like Tangerine Dream and Kraftwerk were on the cutting edge of rock music. Tangerine Dream was still avant-garde in an old-fashioned way. The drone might be synthesized but the wail was still the mystical siren song of Hendrix's acid-soaked guitar. Tangerine Dream made a hippyish attempt to humanize technology. They were a Modernist science fiction band. Their populism is obvious in the fact that they added guitar solos to their live concerts - a kind of gesture of contact with their rock audience. In fact, no one needed to be on stage to perform Tangerine Dream's music. The machines could do it themselves, if they were allowed to. Kraftwerk, on the other hand, like the Pop Art-inspired Roxy Music in England, were cool and ironic. Their synth work was meant to be overtly kitsch - a modernist joke. How could it not be? The Moog had already become the more up-to-date replacement for the Wurlitzer organ: a wondrous machine to charm the lower classes with its power to mimic and make exotic the worn-out. Every old musical chestnut, from easy-listening mush to classical music to hard rock was available in "switched on" versions. Like the Theramin before it, the synthesizer quickly fell from grace as the great technological hope that would change music, to become a humorous "specialty" instrument used for novelty records and fantasy soundtracks. Kraftwerk mined this kitsch potential to produce phony "art" music. Unlike Tangerine Dream they would never sink to such proletarian populist gestures as a live guitar solo. Sometimes, in fact, their music would be performed on stage by showroom dummies that stood immobile in front of the self-operating machines. Populism to Kraftwerk was not heroicized class unity, but a word connoting the infantile products geared toward an infantalized social group. Pop music is inherently kitsch music.

This rock decadence was obviously in the air in the early 70s, in the states as well as in Europe. At the Ann Arbor Film Festival, sometime in the mid 70s, I saw a short comedic promotional film (a kind of precursor to a rock video) by a group called Devo (short for de-evolution). I was very impressed with Devo's whole package: their adoption of everything that was hated in rock music at the moment. They ditched the macho lead singer of boogie rock for a pudgy costumed nerd "Boogi Boy', who would sometimes perform in a playpen making overt the infantilist nature of rock music. Rock music: industry produced pabulum for the masses. Every rock band was the Monkees in their eyes. This industrial aesthetic was overt in their packaging of themselves: that they were a "corporation" not a band, that they did overt promotional commercials for themselves, made dysfunctional by stripping away all of the sexualized glamour that was there in both rock and disco. I don't think a band like this could have come out of Detroit because of the city's rich history of class-conscious rock culture. Detroiters were embarrassed. There was such an important history there to mine: the Psychedelic Stooges, MC5, SRC, Amboy Dukes, Alice Cooper, Früt - all important local bands during my junior high school years. But now, there was not one single good rock band in Detroit. Detroit, like all of the other industrial cities of the Midwest had died an ignoble death. But Detroit still had its cultural pride; it was still "Rock City" (to quote Kiss). Detroit was pathetically in denial. It makes perfect sense that Ohio would be the place that a vibrant grunge scene would spring up. Buckeyes were more willing, and able, to see the cultural death surrounding them and to capitalize on it. Besides Devo, Ohio produced Pere Ubu, a less ironic band whose approach to the "industrial" aesthetic was to adopt the tonalities of the gothic sublime the romance of the ruin applied to the dead husk of Modernist industrialization. No, in Ohio there was no glorious past music history to get in the way - inn Detroit, on the other hand, it seemed as if the world had ended, and all outside communication to whatever small outposts were left was cut off. Destroy All Monsters operated in this vacuum. We truly thought we were the only ones doing what we were doing.

In a way, Destroy All Monsters are a mixture of the two trajectories (prole rock/punk, art rock/techno) I have outlined. We reveled in the death of rock. We gave up straight rock instrumentation by playing mostly old electronic cast-offs, tape recorders and noise makers, but we felt no qualms about using standard rock instruments either - or playing rock cover versions, albeit very fucked up ones. We had slightly artistic and avant-garde pretensions, we were in your face but we also had a sense of humor - albeit a very sour one. And as with the punk rockers, there was a definite class affiliation which we were unwilling to give up, even if we weren't very happy about it. We would, or could, not adopt totally the ultra-cool ironic and commercially packaged stances of Kraftwerk and Roxy Music. The pure noise we cranked out was still moving to us; there were vestiges of the uplifting psychedelic rock aura left about it. Though this might have been apparent only to us and not the average listener. We could hear it. We still were, after all, a Detroit band. We had our cultural pride. And, I was not particularly interested in making sense. All the best bands of my youth were ones that were full of contradictions: Captain Beefheart, the Stooges, the Doors, the Velvet Underground, early Pink Floyd. All of these bands were simultaneously ironic and heartfelt, funny and serious, pop and experimental, lowbrow and highbrow. They were hard to figure out.

After I moved to Los Angeles in 1976 I discovered that there indeed were other bands working in the world who had somewhat the same interests as Destroy All Monsters: Suicide, Airway, Pere Ubu, Throbbing Gristle, Half Japanese, Devo, the Screamers, Non, the Residents and such New York No Wave groups as Teenage Jesus and the Jerks and DNA. All of these bands were of interest to me. I, however, found the L.A. scene not very supportive of this type of ugly noise and I quickly gave up the idea of continuing in bands. I began to do solo performance work geared toward an art audience. L.A. was dominated by hardcore and British-style punk. Destroy All Monsters, as it still existed in Detroit, switched directions after Ron Asheton came into it, going after more of a hard rock sound. And soon the only original member left in Destroy All Monsters was Niagara, on vocals. This band bears no similarity to early DAM and belongs solely within the confines of a punk rock history.

PART II

Destroy All Monsters was formed in Ann Arbor Michigan in the winter of 1974. The founding members were: Cary Loren, Mike Kelley, Niagara, and Jim Shaw. Niagara, Shaw, and myself met as students at the art school at the University of Michigan in 1972.

Niagara was one of the first persons I met upon my arrival in Ann Arbor in 1972. I got onto a bus giving new students an orientation tour of the U of M Campus and was immediately struck with her beauty. She stood out from the busload of typical hippie youth as a dark star. She was a freak, no doubt about it. Pale, introverted, and trashy, she looked like some sort of B Movie star - a sickly anti-blonde Marilyn Monroe, the negative reversal of healthy sex kitten Marilyn. Niagara had a reciprocal beauty, fed by Nyquil, Tab and Sanders' chocolate cake. She was what Anita Pallenberg was to Jane Fonda in Barbarella. The dead Marilyn, as filtered through the decadence of Warhol's factory was very important to Niagara I was to find out. At this point Niagara was not yet Niagara. She had not yet given up her "slave name" ala Malcolm X to take on her new name derived from an old Marilyn movie. At this point Niagara was sequestered away in an all girl dormitory that made her difficult to visit. Unlike other dorms where you could walk right in and knock on the door, in this one you had to call ahead and make a reservation, very formal. At least this is how I remember it, though this might be an example of false memory syndrome wish fulfillment. Even so, it adds to my construction of Niagara as a remote and unreachable ideal - a surrealist girl. It turned out we were both in art school and shared some first year classes. I remember specifically being in a life drawing class with her. I do not, however, remember her ever drawing from the models. Instead, she did small delicate watercolors reminiscent of 19th century fairy tale illustration. They were not the flowery hippie sort that I was familiar with, the kind filled with mushrooms, rainbows and unicorns. Niagara's drawings were a scarier, more darkly realistic version of this aesthetic - one that might now be called "gothic". They were the bad acid trip, somehow appropriate to a town where a major university building was named after Arthur Rackam. But, sadly, even if someone in the dim past had felt like paying homage to Rackam by naming a portion of the University after him, Rackam 's aesthetics themselves were not given much respect in the School of Art. I am fairly sure that Niagara did not attend art school after this first year. She never quite seemed to be there in any purposeful way anyway. Niagara had already developed her own aesthetic, so it only seemed natural when she dropped out of school.

Some of Niagara's drawings included a nude male figure with long dark hair. This was her mysterious friend Cary, who she spoke of often. Cary Loren soon moved to Ann Arbor to join Niagara. They got an apartment not far from where I now lived, myself having also gotten out of my dorm (though not out of school). I would visit them there to listen to records and see the various items, the interesting trash, that they would collect off the street to decorate their home with. Cary made trash art - odd lumpen sculptures made of brightly painted papier mache which reminded me of the kinds of disturbing biomorphic forms found in paintings by Arshile Gorky as would be produced in a elementary school art class. He also made evil psychedelic collages on posterboard composed of low imagery cut from magazines intermixed with pulpy peaks of painted papier mache and small objects, such as bits of cheap jewelry and plastic trinkets from bubble gum machines. This street trash aesthetic extended into the social as well as the artistic, with the collection and documentation of Ann Arbor's rich street people community. Cary would post flyers on telephone poles around Ann Arbor advertising a free party. When the resulting strange mix of people showed up, the event was documented on film. Cary made film collages as well, utilizing cutup commercial super 8 films and his own films of deviant behavior by his friends and young relatives, as well as more abstract stop motion animated films of common objects, like light bulbs, moving about. He also was constantly taking photographs and making audio recordings on a cheap portable cassette recorder. His photographs where especially interesting and ranged from close up still lives of small odd objects, to set up tableaus utilizing his friends that looked like dysfunctional perfume adds, to photos of Niagara: Niagara in underwear laying in a pool of blood at the bottom of a cellar stairway, or Niagara as a murderous vixen ala a cheap Mexican movie, or Niagara in gloomy cheesecake photos looking somewhat like Vampira, all looking as if they had been clipped from the pages of Police Detective magazine. He also made zines and chapbooks of his own writings, much of which was inspired by the imagery of Jack Smith (Cary every once in a while alluded to a mysterious episode when he ran off to New York to live at Jack Smith's Lower East Side plaster palace). Cary interfaced with the world through media. It was as if he took Warhol's novel A

(a verbatim transcription of "superstar" Ondine's conversations in the course of one day) as the model for his life. Daily life was art, and it should all be recorded. Interestingly, it was the act of recording, more than the final product, which was of interest. There was little attention paid to the quality of the various recordings themselves. Photographs, which he printed himself in a home darkroom, were poorly printed and fixed improperly so they soon faded, audio was taped on the cheapest cassettes (mostly used cassettes bought second hand or K-Mart brand three-pack cheapies). Daily life filtered through the media immediately became trash itself. Trash was life.

I lived a couple of blocks away in a three-story Victorian house housing a large enough group of freaks to make the rent affordable to everyone. I think around seven or eight people lived there. I moved into the basement, which cost me between 40 and 50 dollars a month. This house, it could be called a commune except no one shared anything, was called God's Oasis Drive In Church because a sign saying as much was nailed to the front porch. This sign was just one of many oddities that the house was museum to. The place reminded me of the Adam's Family home. Jim Shaw, who also lived in the house, had found most of these cultural cast-offs. Jim had a bloodhound's nose for weird things. He was dedicated to finding them. Garage sales and thrift stores were magnets to him. Unlike Cary, who had a fondness for junk with suburban Pop appeal, Jim went for the most surreal of cultural rejects: the crackpot, the outmoded yet unhip throwaways of all cultural periods. And all of these were piled in one immense heap oozing its way throughout the building. God's Oasis was decorated with a strange mix of 40s overstuffed furniture and flowery print curtains mixed indiscriminately with 50s boomerang pattern curtains, harlequin and ballerina paintings and lamps in the form of maraca-playing Latin musicians, all swamped in a tide of knick knacks and cultural oddities too numerous to list. In fact the house was barely habitable because of the large amount of garbage it was storehouse to.

I had met Jim very soon upon my arrival in art school. I noticed him immediately because of his odd dress. He wore the most amazing things: ladies' stretch pants, message-oriented t shirts that he would hand alter to pervert their uplifting slogans, bits of fast food restaurant uniforms, and a long flasher-type 40s storm coat that had a hump sewn on the back. To this hump he affixed a boy's jacket with award patches; he looked like Charles Manson with a Cub Scout growing out of his back. He was hard to miss. I also quite admired his artwork. Among many other things, he made paintings utilizing various psychosexual images derived from old advertisements mixed together in a seemingly random fashion on top of splatter color fields. These were often painted on top of the same kind of ugly old drapes, stretched over canvas stretchers, that were hanging in the house. The coloration of these paintings was quite dismal and weird, due to the fact that much of the oil paint that they were painted with was scrounged from the garbage can in the art school painting studios, deposited there after other students had scraped it off the pallets. I remember him distinctly using the garbage can itself as a palette, mixing the paint he found there right on the rim of the can. He was fond of the gray/brown sludge that accumulated on the bottom of the communal cans of paint thinner used to clean brushes. This would be used as the ground on which he painted - the primal void, if you will, that the painting cosmos grew out of.

I lived in the basement of God's Oasis. It was a large space, well suited to working and with all the luxuries of a true home - its own slop sink and toilet. My own world. In one corner was a raised concrete slab, about 4 by 8 feet in size. This is the corner where I slept, on an old single-frame metal hospital bed, which seemed appropriate since the basement was painted in fading hospital green. To differentiate my sleeping corner from the rest of the space I painted it pink. Next to my bed was the water heater for the house. The murmur of its pilot light lulled me to sleep at night. This underground enclave was to become the rehearsal room for Destroy All Monsters.

It was at a party in 1974 that the four of us, Jim, Cary, Niagara and myself decided to form a band. It was the natural thing to do, the perfect way to encapsulate the various public actions we were already engaged in. The form was right - popular, people will come see us instead of us having to fool them (this was a strategy Jim had employed before to get people to attend actions of his - he would make false flyers for nonexistent events, a speech by Baba Ram Das for example, to attract an audience). No one, except Cary, had any musical abilities. Cary could play guitar a bit. I went to K Mart with Jim and he bought the cheapest electric guitar you could buy, a Tesco, I think. He proceeded to "prepare" it in the manner of John Cage's pianos, with old tie clips, etc. We went to the organ shop and bought a used drum box to solve the drummer problem. I accumulated odd bits of electronic equipment - cheap electric organs, old PA systems and tape recorders which often would only feed back, and sound producing toys which I would highly amplify. I was a big fan of the way in which the Art Ensemble of Chicago used small sounds: bird calls, rattles, toys, which were put together in a fabric of never ending shifting assortments of little events that punctuated their frenetic shows. These little events, when highly amplified, had the power of heavy metal power chords. Each little sound could be an atomic explosion. Jim named the band. There was not much argument about it. The film, Destroy All Monsters, was loved by us all. It was "the ultimate monster party", the meeting of every Japanese monster on Monster Island to battle it out. This cacophony of bestial battle was what we were after. We loved the sound of Godzilla's roar - that backwards-sounding growl with a subliminal tolling bell buried in it, and the sweet cadences of the singing twins who were the consorts of Mothra. That was the dialectic we were after, Those was truly inspiring musics.

Destroy All Monsters in actuality never was one band but an agreement between two bands to share a name and sometimes perform together. On one side were Cary and Niagara, and on the other were Jim Shaw and I. Cary and Niagara were more interested in song structures and had a love of pop trash, glitter rock and gloom and doom Mansonesque imagery -very "witchy". They were fans of Bowie, T Rex, Roxy Music, the New York Dolls and such. Jim and I were more interested in pure noise and had little interest in bothering with song structures or pop licks, except as simple book-ending devices for the noise - like free jazz players, Coltrane for instance, would use pop standards such as Disney tunes to build off of and eventually fuck up and distort. Our tastes were somewhat different. Jim had a soft spot for gothic sweetness. He liked to listen to the death folk of the Incredible String Band, John Fahey, and the more depressing folksy Led Zepplin songs, and even pomp rock like Yes, which I could not stomach. Yet we did share a love of psychedelia and Sun Ra. At this time I was listening mostly to free jazz: Albert Ayler, Archie Shepp, the Art Ensemble, etc, and to German psychedelia and trance music: Popul Vuh, Can, Terry Riley. But there were a few things all of us could all agree on, and that was the noise rock of the first MC5 album, the Stooges, and the Velvet Underground. Those bands allowed for both the factory-driven pulse of metal and the electric wail of pure noise. Cary and Niagara began to write songs, Jim and I set up a situation where there was constant noise improvisation.

This structure did not allow for elaborately worked-out product. Instead, we would pick a situation, and just show up and play. We did not play publicly very much for the simple fact that there was no place to do so, and no audience for the kind of thing we were doing. Our first gig was at a comic book convention. We were not invited. We simply crashed the event, set up and played. This was how we got the majority of our gigs. We asked the band to use their PA system but after one song, a variation on Black Sabbath's Iron Man, we were asked to leave. We also played a Halloween show at the U of M art school where we did a minimalist version of Shaking All Over, the loft of local jazz musician Gerhard Schlanzky, and several private parties one gig consisted only of an endless trance version of "Nature Boy." These are the only public gigs I can remember; though we also played quite often at open parties held at God's Oasis. Sometimes it would just be the God's Oasis half of the band, where Jim and I would be joined by some of the other peoples who lived at the house: John Reed on guitar, Kalle Nemvalts on trumpet or Dave Owen on clarinet. These were pure noise-fests dominated primarily by Jim Shaw's huge walls of distorted guitar feedback, and my other varied noise products: squealing amplified toys, saxophone or voice, tape effects, bashing metal and drums, etc. When Cary and Niagara joined us, we would try to accompany their gloomy lyrics (songs like: I'm Dead, You're Going to Die, I'm Bored, Acid Monster) as best we could, with me sometimes on drums and Niagara on scratchy John Cale-inspired violin. Cary and Niagara would take turns on the various songs. Cary had the better voice: a Jim Morrisonesque low tone, but Niagara was the center of attention. Niagara's anti-stage presence was captivating. Her emotionless monotone made Nico sound like a screamer, and generally she sang so softly you could barely hear her over the din. Oftentimes she would sing seated, facing away from the audience, and in one memorable show, she lay on the floor in a fetal position with her head on the pillow inside of the bass drum, letting out a pitiful cry every time the bass was struck, yet unwilling, or unable, to get up.

Not surprisingly, our music was pretty much despised. There was, at most, an audience of 50 people who had any interest in noise music in the Detroit area at that time. All of the members of Destroy All Monsters had grown up during the alternative cultural renaissance of the late Sixties. We had all been raised on the psychedelic excesses of the MC5 and the Stooges, and the general feeling of that time: that every form could be combined and all excesses were possible. Now we were in the dark ages. Detroit's economy had collapsed and taken with it its radical culture. Detroit was a dead city. And Ann Arbor, once the "drug capital of the Midwest", Eden to every unhappy teen-age runaway, home of the SDS, the White Panther Party, and a thriving radical intellectual scene, was now slipping back into being a sleepy and conservative fraternity-row college town. All of the musicians of the previous generation were trying to adapt to the cleaner hard rock sound of the day. Fred Smith's Sonic Rendezvous Band and Ron Asheton's New Order were dull plodding outfits, trying to match the success of Ted Nugent. I believe they were embarrassed at the psychedelic extravagances of their youth. And those of our own age were basking in the mellow sounds of country rock and the tired noodlings of the Alman brothers and the Grateful Dead. Things were very depressing. This was the milieu that birthed Destroy All Monsters. We were designed to be a "fuck you" to the prevailing popular culture.

I, personally, saw no future in it and left for California to attend graduate school, soon followed by Jim Shaw. After our departure, Cary brought Ron Asheton into the band. The trials and battles of that group are another story - though a quite interesting one, and I'll leave that to the participants to tell.

Mike Kelley

1993

(Destroy All Monsters: 1974/77)

Some thoughts on the period of transition from progressive rock to punk rock, in the form of liner notes for a three CD box set.

PART 1

Music is eternal; it is ahistorical. So says the polliwog. Music in time is Muzak: floating strains, the meaningless pap that provides the background soundtrack for other peoples lives. It lies behind those that have history, who are old. Like embarrassing cartoon music, this mush shows its age and, in an amusing way, provokes disgusted looks on the enfeebled listeners who are familiar with it, who once thought that it was impervious to cooption. How pathetic . . . to hear these once "hot" sounds demoted to punctuation for children's entertainments, to be made present again . . . but only for the pre-adolescent. This is what happened to Raymond Scott's "Powerhouse" when applied to Bugs Bunny, when Cab Calloway crooned along with Betty Boop, and even now when Jimi Hendrix, in his death, supplies the soundtrack for today's "adult toy" car commercial. It is said that the old always return to their original childlike state, unless they are lucky enough to die first; they sink back to the square-one level of powerlessness. This deflation in caused by the realization that one is in time. Then the potent fuck beats of your prime become limply infantile. I am speaking now from the vantage- point of the old frog. And I tell you, once you have a music history these observations are painful and obvious facts. To the young soul these are incomprehensible notions. To these naives, music is of the moment. There is evolution, but in a constant present . . . always in a state of becoming. Changing reactions to music, and conscious improvements in taste, are not made in reference to a time before but are simply realizations that something could, not . . . be different, but better. New music is an outgrowth - a living thing emerging from a vibrant parent body and not a sickly response to that which has passed away. These sad observations are provided as an around-about way to introduce the genesis of a band, a band that never was - Destroy All Monsters, and to reveal some of the problematics of that attempt.

For me, these old recordings from 1974/76 are still very present. When I listen to them I am again back at their point of creation - because they never came to a conclusion. The "history" that they are part of is not yet written, at least not adequately. I am quite aware of the reasons for their production, and also the reasons why they are, perhaps, failed attempts. I also realize that the general listener will, more than likely, not understand them at all. This puts me in the position of having to construct a history for them, to set them up to age. And I sincerely hope they do become familiar enough to suffer the embarrassment of their position in time . . . to be used in cartoons and soft drink commercials. Why not? Everything else has. To set this process in motion means I must separate myself from my "pure" experience of this noise (which I hope still has the capacity to move other listeners in some approximately similar "pure" sense). I will now attempt to explain these recordings into historical importance, and through this explanation convince you that they are not mere kitsch, that they are still alien enough to be worth examining.

Destroy All Monsters is a band that never was, because it is a band that has become historicized (whatever minor history it does have) in an incorrect way. Destroy All Monsters is generally a footnote in the history of American Punk rock. It has been described in terms of, either, an American proto-Punk history (as an outgrowth of the Stooges because of the presence of ex-Stooges guitarist Ron Asheton in the line-up starting in the late 70s); or as a post-British Punk reaction . . . as one of the many bands to spring up in the States in response to the Sex Pistols. These pigeonholings are dependent on the point in time in which the chronicler became familiar with the band, and also their knowledge of American pre-Punk rock music. To many writers, Punk history is automatically a British history, and whatever manifestations of it that may have occurred in America are only twisted reflections of the real thing. In a sense I agree with this interpretation. The American bands that were influential in the development of British Punk: the Stooges, the New York Dolls and the Ramones, were indeed minor American bands in there own times, without any of the celebration and critical response that the Sex Pistols garnered. And second-string American Punk, especially California Hardcore, was obviously more of an outgrowth of the media-conscious and fashionable Sex Pistols than Midwestern and East Coast garage rock of the late 60s and early 70s. I know this for a fact since I was in L.A. in the late 70s. The scene was primarily Glam oriented when Punk hit, like a disease - a British germ that infected everyone overnight. One day there was no Punk, the next day the city was crawling with torn-clothed, safety-pinned spike heads. In any case, this discussion of Punk as the British Invasion of the late 70s has little to do with Destroy All Monsters, which was already in existence in 1974. We were completely ignorant of the British underground musical developments then in a protean neighborhood state of development . . . just like we were. Warning! To all Anglophiles, this is a history that predates the American popularization of punk. And this history only finds its flowering in a later, supposedly post-Punk development - namely, Industrial music. Warning! Also to Stoogeophiles. This is a history of Destroy All Monsters before the arrival of Ron Asheton. Stooges fan club members will not find any missing nuggets of wisdom here.

To understand Destroy All Monsters one must put themselves into an early 70s mindset. The first wave of alternative rock, and by this I mean the incredible outpouring of garage Psychedelia in the late 60s, was long dead by this time. Musically, this was the era of broken promises. The psychedelic avant-garde vision of a new Pop Music to mimic the new social experiment had proven a pipe dream. There was the sense of living in the decadent twilight occasioned by this fall. And in the mindless flight from this Altamontian negativity a wave of escapist feel-good pap became the dominant musical trend. The music scene was dominated by pseudo-back-to-folk-roots ballads of the James Taylor (or one of his innumerable siblings) variety. The thunderous counter-movement to this laid-back sound was prole-rock. Heavy Metal, despite its surface difference from Folk and Country rock, was similarly "roots rock", though admittedly a more high energy and body-conscious version of it. Yet, it was still a music that was meant to console "the people", not confront them.

In this cultural Suburban wasteland there was only isolation, and a sense of being betrayed. The strange brew of avant-garde experimentation and populism of late 60s acid rock had failed in its social promises. To someone of my age (too young to be a hippie, to old to be a punk) there was definitely a feeling of resentment at having missed the short hedonistic flowering of this dream. These fantasies were only then available on records stolen at K Mart or the mall along with other packaged fantasies: Conan the Barbarian novels and other adolescent juvenilia. And by the time you got these records, the "stars" who made them were already in decline: dead, drugged out, or producing corporate rock. Where was my utopia? Where was my free sex? Nowhere to be seen. It only existed in a corporate dream of packaged freedom, in the pathetic sense that thirteen-year-olds wish to be the eighteen-year-olds they see in movies - movies like "Pretty Poison," where hot teen-age girls snuff their parents and put the blame on a nerd. But, I was the nerd. Because of this overall mood of betrayal, rock music was something to be abandoned and left to the dolts: the new armies of ex-high school football players, now hipster longhairs, who filled stadiums to see "righteous" acts like Grand Funk. In revenge for this betrayal, in revenge for the popularization of rock music, for the rise of arena rock, for the rise of country rock, the most moronic musics of the progressive acid rock period of the late 60s all of a sudden seemed its most important products. The thuggish sounds of the Stooges, Blue Cheer and the insipid acid-whinings of the Seeds revealed the pomposity of the "grand experiment". Thirteen-year-old-music of the late 60s became more important than the technically superior and politically savvy music of the twenty-year olds. "Progressive" English and San Francisco rock was abandoned. Inspirational noise had to be found elsewhere. Even in high school, before any of the self-conscious "criticality" of college, I had these leanings. Even then, I found myself tiring of rock music and explored it in its furthest outposts, where the definition of "rock" was stretched beyond recognition. Noise fests like the weird "songs" by Silver Apples, the more annoying Pink Floyd tunes like "Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun", the MC5s "Starship", the Stooges "L.A. Blues", the Mothers of Invention' "Weasels Ripped my Flesh" the Velvet Underground's "Sister Ray" were my preferred listening. These oddities led to the realization that there was "another" history behind these records, a much more brutal, and anti-pop, history that deserved looking into. Brutality, cutting through the pop boundary line, seemed to be the order of the day. Thus I was led to Sun Ra, Morton Subotnik, Harry Partch, Lamont Young, John Cage, Stockhausen, Dadaist Bruitism, and the Futurist noise music theories of Luigi Russolo. Rock was a thing of the past. Disco music was already starting to eclipse it in popularity. I was convinced that what had been interesting in Rock all along was just the volume, your physical response to it. Everything else was just packaging - the marketing strategies necessary to sell pop product.

Georgio Morodor was God and Donna Summer his feminine voice, a voice that only feels the need to speak in orgasms. The first time I heard "I feel Love", it was a revelation. Here was a pure example of pop strategizing. All musicianship was removed; all pretenses to avant-garde theorizing as exemplified by rock acts like the Jimi Hendrix Experience which, to preach their message of freedom, had to make the listener un-free. By that I mean . . . Progressive Rock required a god-like technician, a skilled adept that, like the catholic priest, was a necessary intermediary between you and the "truth". This focus on technical expertise produced the "Rock God" - the guitar hero. Though, at this point, before the rise of codified Heavy Metal guitar worship, there was still a symbiotic relationship between musician and listener. In psychedelic music this relationship centered on feedback and random noise, which equalized musician and listener. Feedback was a sign that the musician was out of control, and the musician and listener shared equally in their experience of this out-of-control state. Feedback was the revolutionary component of acid rock, the anarchic sign of revolutionary freedom. It is the product of the electric instrument monitoring itself, and this self-examination leads to a breakdown of control that is evidenced in the mantra of the feedback loop - the technical equivalent of the acid trip. This was the same sound produced by the Free Jazz saxophone player. The instrument becomes the voice speaking in tongues; it is a pure extension of the voice. The wail of the saxophone is the voice and instrument mirroring each other, eyeing each other, feeling each other out until the one and the other are indistinguishable.

After the fall of the acid rock religion and the loss of faith in its revolutionary signifiers feedback, as a sign, became suspect. The voice no longer seemed an especially true voice. In Morodor's Techno Pop, feedback is synthesized, is domesticated, it becomes pseudo-feedback. What had been hot became cool. And with this change the various categories of rock music as they had existed no longer made sense. Progressive rock became "art" rock - that is, "fake" rock. The digital sequencer roar of Georgio Morodor is feedback harnessed, anarchy pantomimed a confusing contradiction of terms. It is push button rebellion. Yet, oddly, pseudo-feedback still has the same physical effect on the listener as the real thing. Now, the rock god became disposable and the religified communion produced by the relationship between musician and listener, the unequal relationship of devotee to idol, could be rejected. In progressive rock, the technical virtuoso allows you to commune with god only through them. They reveal their equality with you through the symbolic "failure" of feedback. Their "mistake" reveals them, like Jesus, to be also mere man. But with the mechanization of chaos there is no need of a technical virtuoso to symbolically fail. Everyone is equalized automatically because no technical skills are needed. And with this erasure of upper and lower, so also the mystical aspects of rock music are undone. Rock becomes materialistic; its effects have to be explained in somatic terms. If some rock was still "progressive" this term must now be expanded to accommodate market discourse. The question now is: what separates progressive materialist rock from corporate materialist rock?

With the demystification of rock music, its "artistry" shifts away from its truth-value to its codes of irony. The new cognoscenti are those who are steeped in the dictionary of the signs of rock's commodification. Rock stripped of its political trappings becomes, like early rock and roll of the Chuck Berry sort, linked with the purely hedonistic. Except that it is no longer associated with the lower classes, it becomes an intellectual property. This is implicit in the ironic Eurotrash posturings of Roxy Music. Rock now is simply a sign of the "trendy"; it is pure image. Rock becomes a word put to something to signify its acceptability. Avant-garde bands like Tangerine Dream and Kraftwerk all of a sudden were acceptable to large audiences of teens once they packaged themselves as a rock bands and separated themselves from the intellectual ghetto of electronic music. After "I Feel Love" it was apparent that all you needed to produce a pop hit was a machine rhythm and a sexualized image. Techo Pop (and Punk, Techno Pop's sloppy cousin) were born. Punk was born out of this same freedom from virtuosity. Punk shared Techno Pop's rejection of virtuosity, but also rejected the intellectual removal and irony of this gesture as seen in Art Rock bands such as Roxy Music, Kraftwerk and Devo. Anti-virtuosity was a democratic, populist gesture in favor of a decadent one. The pop hooks and guitar solos of prole rock might have been dismissed, but not the class affiliation, and the musical signifiers of that class: guitar, bass and drums.

The German bands were the most willing to play with and extend rock signifiers, perhaps because it was not a music born there and the class ties were not so strong. In the early 70s German trance bands like Tangerine Dream and Kraftwerk were on the cutting edge of rock music. Tangerine Dream was still avant-garde in an old-fashioned way. The drone might be synthesized but the wail was still the mystical siren song of Hendrix's acid-soaked guitar. Tangerine Dream made a hippyish attempt to humanize technology. They were a Modernist science fiction band. Their populism is obvious in the fact that they added guitar solos to their live concerts - a kind of gesture of contact with their rock audience. In fact, no one needed to be on stage to perform Tangerine Dream's music. The machines could do it themselves, if they were allowed to. Kraftwerk, on the other hand, like the Pop Art-inspired Roxy Music in England, were cool and ironic. Their synth work was meant to be overtly kitsch - a modernist joke. How could it not be? The Moog had already become the more up-to-date replacement for the Wurlitzer organ: a wondrous machine to charm the lower classes with its power to mimic and make exotic the worn-out. Every old musical chestnut, from easy-listening mush to classical music to hard rock was available in "switched on" versions. Like the Theramin before it, the synthesizer quickly fell from grace as the great technological hope that would change music, to become a humorous "specialty" instrument used for novelty records and fantasy soundtracks. Kraftwerk mined this kitsch potential to produce phony "art" music. Unlike Tangerine Dream they would never sink to such proletarian populist gestures as a live guitar solo. Sometimes, in fact, their music would be performed on stage by showroom dummies that stood immobile in front of the self-operating machines. Populism to Kraftwerk was not heroicized class unity, but a word connoting the infantile products geared toward an infantalized social group. Pop music is inherently kitsch music.

This rock decadence was obviously in the air in the early 70s, in the states as well as in Europe. At the Ann Arbor Film Festival, sometime in the mid 70s, I saw a short comedic promotional film (a kind of precursor to a rock video) by a group called Devo (short for de-evolution). I was very impressed with Devo's whole package: their adoption of everything that was hated in rock music at the moment. They ditched the macho lead singer of boogie rock for a pudgy costumed nerd "Boogi Boy', who would sometimes perform in a playpen making overt the infantilist nature of rock music. Rock music: industry produced pabulum for the masses. Every rock band was the Monkees in their eyes. This industrial aesthetic was overt in their packaging of themselves: that they were a "corporation" not a band, that they did overt promotional commercials for themselves, made dysfunctional by stripping away all of the sexualized glamour that was there in both rock and disco. I don't think a band like this could have come out of Detroit because of the city's rich history of class-conscious rock culture. Detroiters were embarrassed. There was such an important history there to mine: the Psychedelic Stooges, MC5, SRC, Amboy Dukes, Alice Cooper, Früt - all important local bands during my junior high school years. But now, there was not one single good rock band in Detroit. Detroit, like all of the other industrial cities of the Midwest had died an ignoble death. But Detroit still had its cultural pride; it was still "Rock City" (to quote Kiss). Detroit was pathetically in denial. It makes perfect sense that Ohio would be the place that a vibrant grunge scene would spring up. Buckeyes were more willing, and able, to see the cultural death surrounding them and to capitalize on it. Besides Devo, Ohio produced Pere Ubu, a less ironic band whose approach to the "industrial" aesthetic was to adopt the tonalities of the gothic sublime the romance of the ruin applied to the dead husk of Modernist industrialization. No, in Ohio there was no glorious past music history to get in the way - inn Detroit, on the other hand, it seemed as if the world had ended, and all outside communication to whatever small outposts were left was cut off. Destroy All Monsters operated in this vacuum. We truly thought we were the only ones doing what we were doing.

In a way, Destroy All Monsters are a mixture of the two trajectories (prole rock/punk, art rock/techno) I have outlined. We reveled in the death of rock. We gave up straight rock instrumentation by playing mostly old electronic cast-offs, tape recorders and noise makers, but we felt no qualms about using standard rock instruments either - or playing rock cover versions, albeit very fucked up ones. We had slightly artistic and avant-garde pretensions, we were in your face but we also had a sense of humor - albeit a very sour one. And as with the punk rockers, there was a definite class affiliation which we were unwilling to give up, even if we weren't very happy about it. We would, or could, not adopt totally the ultra-cool ironic and commercially packaged stances of Kraftwerk and Roxy Music. The pure noise we cranked out was still moving to us; there were vestiges of the uplifting psychedelic rock aura left about it. Though this might have been apparent only to us and not the average listener. We could hear it. We still were, after all, a Detroit band. We had our cultural pride. And, I was not particularly interested in making sense. All the best bands of my youth were ones that were full of contradictions: Captain Beefheart, the Stooges, the Doors, the Velvet Underground, early Pink Floyd. All of these bands were simultaneously ironic and heartfelt, funny and serious, pop and experimental, lowbrow and highbrow. They were hard to figure out.

After I moved to Los Angeles in 1976 I discovered that there indeed were other bands working in the world who had somewhat the same interests as Destroy All Monsters: Suicide, Airway, Pere Ubu, Throbbing Gristle, Half Japanese, Devo, the Screamers, Non, the Residents and such New York No Wave groups as Teenage Jesus and the Jerks and DNA. All of these bands were of interest to me. I, however, found the L.A. scene not very supportive of this type of ugly noise and I quickly gave up the idea of continuing in bands. I began to do solo performance work geared toward an art audience. L.A. was dominated by hardcore and British-style punk. Destroy All Monsters, as it still existed in Detroit, switched directions after Ron Asheton came into it, going after more of a hard rock sound. And soon the only original member left in Destroy All Monsters was Niagara, on vocals. This band bears no similarity to early DAM and belongs solely within the confines of a punk rock history.

PART II

Destroy All Monsters was formed in Ann Arbor Michigan in the winter of 1974. The founding members were: Cary Loren, Mike Kelley, Niagara, and Jim Shaw. Niagara, Shaw, and myself met as students at the art school at the University of Michigan in 1972.

Niagara was one of the first persons I met upon my arrival in Ann Arbor in 1972. I got onto a bus giving new students an orientation tour of the U of M Campus and was immediately struck with her beauty. She stood out from the busload of typical hippie youth as a dark star. She was a freak, no doubt about it. Pale, introverted, and trashy, she looked like some sort of B Movie star - a sickly anti-blonde Marilyn Monroe, the negative reversal of healthy sex kitten Marilyn. Niagara had a reciprocal beauty, fed by Nyquil, Tab and Sanders' chocolate cake. She was what Anita Pallenberg was to Jane Fonda in Barbarella. The dead Marilyn, as filtered through the decadence of Warhol's factory was very important to Niagara I was to find out. At this point Niagara was not yet Niagara. She had not yet given up her "slave name" ala Malcolm X to take on her new name derived from an old Marilyn movie. At this point Niagara was sequestered away in an all girl dormitory that made her difficult to visit. Unlike other dorms where you could walk right in and knock on the door, in this one you had to call ahead and make a reservation, very formal. At least this is how I remember it, though this might be an example of false memory syndrome wish fulfillment. Even so, it adds to my construction of Niagara as a remote and unreachable ideal - a surrealist girl. It turned out we were both in art school and shared some first year classes. I remember specifically being in a life drawing class with her. I do not, however, remember her ever drawing from the models. Instead, she did small delicate watercolors reminiscent of 19th century fairy tale illustration. They were not the flowery hippie sort that I was familiar with, the kind filled with mushrooms, rainbows and unicorns. Niagara's drawings were a scarier, more darkly realistic version of this aesthetic - one that might now be called "gothic". They were the bad acid trip, somehow appropriate to a town where a major university building was named after Arthur Rackam. But, sadly, even if someone in the dim past had felt like paying homage to Rackam by naming a portion of the University after him, Rackam 's aesthetics themselves were not given much respect in the School of Art. I am fairly sure that Niagara did not attend art school after this first year. She never quite seemed to be there in any purposeful way anyway. Niagara had already developed her own aesthetic, so it only seemed natural when she dropped out of school.

Some of Niagara's drawings included a nude male figure with long dark hair. This was her mysterious friend Cary, who she spoke of often. Cary Loren soon moved to Ann Arbor to join Niagara. They got an apartment not far from where I now lived, myself having also gotten out of my dorm (though not out of school). I would visit them there to listen to records and see the various items, the interesting trash, that they would collect off the street to decorate their home with. Cary made trash art - odd lumpen sculptures made of brightly painted papier mache which reminded me of the kinds of disturbing biomorphic forms found in paintings by Arshile Gorky as would be produced in a elementary school art class. He also made evil psychedelic collages on posterboard composed of low imagery cut from magazines intermixed with pulpy peaks of painted papier mache and small objects, such as bits of cheap jewelry and plastic trinkets from bubble gum machines. This street trash aesthetic extended into the social as well as the artistic, with the collection and documentation of Ann Arbor's rich street people community. Cary would post flyers on telephone poles around Ann Arbor advertising a free party. When the resulting strange mix of people showed up, the event was documented on film. Cary made film collages as well, utilizing cutup commercial super 8 films and his own films of deviant behavior by his friends and young relatives, as well as more abstract stop motion animated films of common objects, like light bulbs, moving about. He also was constantly taking photographs and making audio recordings on a cheap portable cassette recorder. His photographs where especially interesting and ranged from close up still lives of small odd objects, to set up tableaus utilizing his friends that looked like dysfunctional perfume adds, to photos of Niagara: Niagara in underwear laying in a pool of blood at the bottom of a cellar stairway, or Niagara as a murderous vixen ala a cheap Mexican movie, or Niagara in gloomy cheesecake photos looking somewhat like Vampira, all looking as if they had been clipped from the pages of Police Detective magazine. He also made zines and chapbooks of his own writings, much of which was inspired by the imagery of Jack Smith (Cary every once in a while alluded to a mysterious episode when he ran off to New York to live at Jack Smith's Lower East Side plaster palace). Cary interfaced with the world through media. It was as if he took Warhol's novel A

(a verbatim transcription of "superstar" Ondine's conversations in the course of one day) as the model for his life. Daily life was art, and it should all be recorded. Interestingly, it was the act of recording, more than the final product, which was of interest. There was little attention paid to the quality of the various recordings themselves. Photographs, which he printed himself in a home darkroom, were poorly printed and fixed improperly so they soon faded, audio was taped on the cheapest cassettes (mostly used cassettes bought second hand or K-Mart brand three-pack cheapies). Daily life filtered through the media immediately became trash itself. Trash was life.

I lived a couple of blocks away in a three-story Victorian house housing a large enough group of freaks to make the rent affordable to everyone. I think around seven or eight people lived there. I moved into the basement, which cost me between 40 and 50 dollars a month. This house, it could be called a commune except no one shared anything, was called God's Oasis Drive In Church because a sign saying as much was nailed to the front porch. This sign was just one of many oddities that the house was museum to. The place reminded me of the Adam's Family home. Jim Shaw, who also lived in the house, had found most of these cultural cast-offs. Jim had a bloodhound's nose for weird things. He was dedicated to finding them. Garage sales and thrift stores were magnets to him. Unlike Cary, who had a fondness for junk with suburban Pop appeal, Jim went for the most surreal of cultural rejects: the crackpot, the outmoded yet unhip throwaways of all cultural periods. And all of these were piled in one immense heap oozing its way throughout the building. God's Oasis was decorated with a strange mix of 40s overstuffed furniture and flowery print curtains mixed indiscriminately with 50s boomerang pattern curtains, harlequin and ballerina paintings and lamps in the form of maraca-playing Latin musicians, all swamped in a tide of knick knacks and cultural oddities too numerous to list. In fact the house was barely habitable because of the large amount of garbage it was storehouse to.

I had met Jim very soon upon my arrival in art school. I noticed him immediately because of his odd dress. He wore the most amazing things: ladies' stretch pants, message-oriented t shirts that he would hand alter to pervert their uplifting slogans, bits of fast food restaurant uniforms, and a long flasher-type 40s storm coat that had a hump sewn on the back. To this hump he affixed a boy's jacket with award patches; he looked like Charles Manson with a Cub Scout growing out of his back. He was hard to miss. I also quite admired his artwork. Among many other things, he made paintings utilizing various psychosexual images derived from old advertisements mixed together in a seemingly random fashion on top of splatter color fields. These were often painted on top of the same kind of ugly old drapes, stretched over canvas stretchers, that were hanging in the house. The coloration of these paintings was quite dismal and weird, due to the fact that much of the oil paint that they were painted with was scrounged from the garbage can in the art school painting studios, deposited there after other students had scraped it off the pallets. I remember him distinctly using the garbage can itself as a palette, mixing the paint he found there right on the rim of the can. He was fond of the gray/brown sludge that accumulated on the bottom of the communal cans of paint thinner used to clean brushes. This would be used as the ground on which he painted - the primal void, if you will, that the painting cosmos grew out of.

I lived in the basement of God's Oasis. It was a large space, well suited to working and with all the luxuries of a true home - its own slop sink and toilet. My own world. In one corner was a raised concrete slab, about 4 by 8 feet in size. This is the corner where I slept, on an old single-frame metal hospital bed, which seemed appropriate since the basement was painted in fading hospital green. To differentiate my sleeping corner from the rest of the space I painted it pink. Next to my bed was the water heater for the house. The murmur of its pilot light lulled me to sleep at night. This underground enclave was to become the rehearsal room for Destroy All Monsters.

It was at a party in 1974 that the four of us, Jim, Cary, Niagara and myself decided to form a band. It was the natural thing to do, the perfect way to encapsulate the various public actions we were already engaged in. The form was right - popular, people will come see us instead of us having to fool them (this was a strategy Jim had employed before to get people to attend actions of his - he would make false flyers for nonexistent events, a speech by Baba Ram Das for example, to attract an audience). No one, except Cary, had any musical abilities. Cary could play guitar a bit. I went to K Mart with Jim and he bought the cheapest electric guitar you could buy, a Tesco, I think. He proceeded to "prepare" it in the manner of John Cage's pianos, with old tie clips, etc. We went to the organ shop and bought a used drum box to solve the drummer problem. I accumulated odd bits of electronic equipment - cheap electric organs, old PA systems and tape recorders which often would only feed back, and sound producing toys which I would highly amplify. I was a big fan of the way in which the Art Ensemble of Chicago used small sounds: bird calls, rattles, toys, which were put together in a fabric of never ending shifting assortments of little events that punctuated their frenetic shows. These little events, when highly amplified, had the power of heavy metal power chords. Each little sound could be an atomic explosion. Jim named the band. There was not much argument about it. The film, Destroy All Monsters, was loved by us all. It was "the ultimate monster party", the meeting of every Japanese monster on Monster Island to battle it out. This cacophony of bestial battle was what we were after. We loved the sound of Godzilla's roar - that backwards-sounding growl with a subliminal tolling bell buried in it, and the sweet cadences of the singing twins who were the consorts of Mothra. That was the dialectic we were after, Those was truly inspiring musics.

Destroy All Monsters in actuality never was one band but an agreement between two bands to share a name and sometimes perform together. On one side were Cary and Niagara, and on the other were Jim Shaw and I. Cary and Niagara were more interested in song structures and had a love of pop trash, glitter rock and gloom and doom Mansonesque imagery -very "witchy". They were fans of Bowie, T Rex, Roxy Music, the New York Dolls and such. Jim and I were more interested in pure noise and had little interest in bothering with song structures or pop licks, except as simple book-ending devices for the noise - like free jazz players, Coltrane for instance, would use pop standards such as Disney tunes to build off of and eventually fuck up and distort. Our tastes were somewhat different. Jim had a soft spot for gothic sweetness. He liked to listen to the death folk of the Incredible String Band, John Fahey, and the more depressing folksy Led Zepplin songs, and even pomp rock like Yes, which I could not stomach. Yet we did share a love of psychedelia and Sun Ra. At this time I was listening mostly to free jazz: Albert Ayler, Archie Shepp, the Art Ensemble, etc, and to German psychedelia and trance music: Popul Vuh, Can, Terry Riley. But there were a few things all of us could all agree on, and that was the noise rock of the first MC5 album, the Stooges, and the Velvet Underground. Those bands allowed for both the factory-driven pulse of metal and the electric wail of pure noise. Cary and Niagara began to write songs, Jim and I set up a situation where there was constant noise improvisation.

This structure did not allow for elaborately worked-out product. Instead, we would pick a situation, and just show up and play. We did not play publicly very much for the simple fact that there was no place to do so, and no audience for the kind of thing we were doing. Our first gig was at a comic book convention. We were not invited. We simply crashed the event, set up and played. This was how we got the majority of our gigs. We asked the band to use their PA system but after one song, a variation on Black Sabbath's Iron Man, we were asked to leave. We also played a Halloween show at the U of M art school where we did a minimalist version of Shaking All Over, the loft of local jazz musician Gerhard Schlanzky, and several private parties one gig consisted only of an endless trance version of "Nature Boy." These are the only public gigs I can remember; though we also played quite often at open parties held at God's Oasis. Sometimes it would just be the God's Oasis half of the band, where Jim and I would be joined by some of the other peoples who lived at the house: John Reed on guitar, Kalle Nemvalts on trumpet or Dave Owen on clarinet. These were pure noise-fests dominated primarily by Jim Shaw's huge walls of distorted guitar feedback, and my other varied noise products: squealing amplified toys, saxophone or voice, tape effects, bashing metal and drums, etc. When Cary and Niagara joined us, we would try to accompany their gloomy lyrics (songs like: I'm Dead, You're Going to Die, I'm Bored, Acid Monster) as best we could, with me sometimes on drums and Niagara on scratchy John Cale-inspired violin. Cary and Niagara would take turns on the various songs. Cary had the better voice: a Jim Morrisonesque low tone, but Niagara was the center of attention. Niagara's anti-stage presence was captivating. Her emotionless monotone made Nico sound like a screamer, and generally she sang so softly you could barely hear her over the din. Oftentimes she would sing seated, facing away from the audience, and in one memorable show, she lay on the floor in a fetal position with her head on the pillow inside of the bass drum, letting out a pitiful cry every time the bass was struck, yet unwilling, or unable, to get up.

Not surprisingly, our music was pretty much despised. There was, at most, an audience of 50 people who had any interest in noise music in the Detroit area at that time. All of the members of Destroy All Monsters had grown up during the alternative cultural renaissance of the late Sixties. We had all been raised on the psychedelic excesses of the MC5 and the Stooges, and the general feeling of that time: that every form could be combined and all excesses were possible. Now we were in the dark ages. Detroit's economy had collapsed and taken with it its radical culture. Detroit was a dead city. And Ann Arbor, once the "drug capital of the Midwest", Eden to every unhappy teen-age runaway, home of the SDS, the White Panther Party, and a thriving radical intellectual scene, was now slipping back into being a sleepy and conservative fraternity-row college town. All of the musicians of the previous generation were trying to adapt to the cleaner hard rock sound of the day. Fred Smith's Sonic Rendezvous Band and Ron Asheton's New Order were dull plodding outfits, trying to match the success of Ted Nugent. I believe they were embarrassed at the psychedelic extravagances of their youth. And those of our own age were basking in the mellow sounds of country rock and the tired noodlings of the Alman brothers and the Grateful Dead. Things were very depressing. This was the milieu that birthed Destroy All Monsters. We were designed to be a "fuck you" to the prevailing popular culture.

I, personally, saw no future in it and left for California to attend graduate school, soon followed by Jim Shaw. After our departure, Cary brought Ron Asheton into the band. The trials and battles of that group are another story - though a quite interesting one, and I'll leave that to the participants to tell.

Mike Kelley

1993